Reveal the risk.

Start the conversation.

Proactive autoantibody detection is helpful to identify individuals who may be in the early stages of autoimmune type 1 diabetes (T1D).1,2

About autoimmune T1D

In 2023, Diabetes Canada estimated that there were 4,118,000 people (representing about 10% of the population of Canada) living with diabetes (type 1 and type 2), where autoimmune T1D represents between 5–10% of the total cases3

Autoimmune T1D is an autoimmune condition characterized by the immune system's destruction of insulin-producing ß-cells in the pancreas.

In autoimmune T1D, the body's immune system mistakenly targets and destroys the ß-cells in the pancreas, which produces insulin.4,5

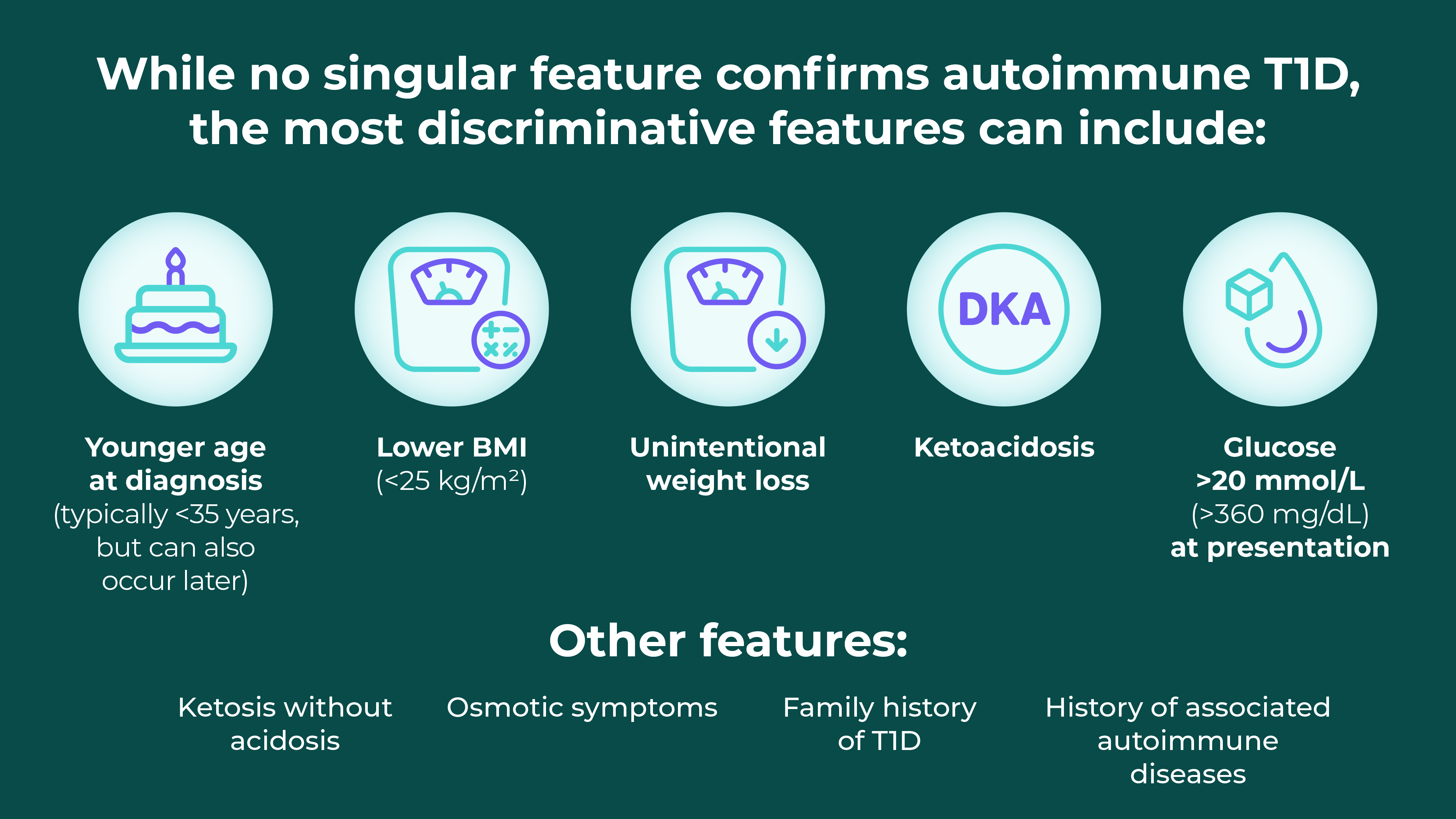

Differentiating autoimmune T1D from type 2 diabetes (T2D)6

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a life-threatening but preventable complication of autoimmune T1D, marked by hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis and ketosis6

The risk factors for DKA can include:

- New diagnosis of diabetes

- Insulin omission

- Infection

- Myocardial infarction

- Abdominal crisis

- Trauma

In addition, there are possible links to continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, thyrotoxicosis, cocaine, atypical antipsychotics and interferon.7

DKA occurs more frequently in autoimmune T1D compared to T2D. The incidence was 4.6–8.0 per 1000 patient-years for people with autoimmune T1D compared to 0.3–2.0 per 1000 patient-years in T2D.7

A Quebec-based surveillance study between 2001 and 2014 found that 25.6% of children aged 1–17 presented with DKA at the time of their diabetes diagnosis (n=1471/5741).8*

Over the study period, the age- and sex-standardized prevalence of DKA at diabetes diagnosis increased from 22.0% (95% CI: 17.3%–27.7%) in 2001 to 29.6% (95% CI: 23.8%–37.1%) in 2014.8

Identifying the signs and symptoms of DKA in your patients

![Clinical presentation of DKA Symptoms Dyspnea (shortness of breath) Nausea Vomiting and abdominal pain Altered sensorium Signs Kussmaul respiration (deep sighing respiration) Acetone-odoured breath Altered sensorium Clinical biomarkers Hyperglycemia (blood glucose >11 mmol/L [200 mg/dL]) Venous pH <7.3 or serum bicarbonate <18 mmol/L Ketonemia (blood beta-hydroxybutyrate concentration ≥3 mmol/L) or ketonuria](/dam/jcr:c80b8204-4c28-4a41-8a5d-66878fd1ef08/ON1305916_TZI_Unbranded_DSE-Website-Tables_EN_r1a-2.png)

Regardless of presentation, a new autoimmune T1D diagnosis can have a substantial impact on affected individuals and their families

Individuals and their families need to adapt quickly to a life with autoimmune T1D, managing lifestyle changes and regular glucose monitoring, with the risk, and potential fear, of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia.10–12

The burden of living with autoimmune T1D can have an impact on quality of life, including mental health disorders.13

|

~300 health-related decisions per day

Breakthrough T1D estimated that life with autoimmune T1D requires a large number of health-related decisions, on average around 300 per day.14 |

|

>$18,000 per year

Diabetes Canada found that out-of-pocket costs for people living with autoimmune T1D can be as high as $18,306 per year in certain areas of Canada. The estimate did not include the potential costs due to loss of productivity or long-term impact of autoimmune T1D.15 |

* The Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System does not distinguish between T1D and T2D.8

- Barker JM, et al. Clinical characteristics of children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes through intensive screening and follow-up. Diabetes Care 2004;27(6):1399–404.

- Elding Larsson H, et al. Reduced prevalence of diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in young children participating in longitudinal follow-up. Diabetes Care 2011;34(11):2347–52.

- Diabetes Canada. Diabetes in Canada 2023 Backgrounder. Available at: https://www.diabetes.ca/DiabetesCanadaWebsite/media/Advocacy-and-Policy/Backgrounder/2023_Backgrounder_Canada_English.pdf. Consulté le 12 juillet 2024.

- Insel RA, et al. Staging Presymptomatic Type 1 Diabetes: A Scientific Statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2015;38(10):1964–74.

- Besser REJ, et al. ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2022: Stages of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes 2022;23(8):1175–87.

- Holt RIG, et al. The Management of Type 1 Diabetes in Adults. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2021;44(11):2589–625.

- Goguen J and Gilbert J. Hyperglycemic Emergencies in Adults. Can J Diabetes 2018;42:S109–14.

- Robinson M-E, et al. Increasing prevalence of diabetic ketoacidosis at diabetes diagnosis among children in Quebec: a population-based retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2019;7(2):E300–05.

- Glaser N, et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Pediatr Diabetes 2022;23(7):835–56.

- Wherret DK, et al. Diabetes Canada 2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada: Type 1 Diabetes in Children and Adolescents. Can J Diabetes 2018:42(Suppl 1):S234–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2017.10.036.

- Yale J-F, et al. Diabetes Canada 2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada: Hypoglycemia. Can J Diabetes 2018:42(Suppl 1):S104–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2017.10.010.

- American Diabetes Association. Chapter 4. Fear of Hypoglycemia (and Other Diabetes-Specific Fears). Available at: https://professional.diabetes.org/professional-development/behavioral-mental-health/MentalHealthWorkbook. Accessed April 3, 2024.

- Robinson DJ, et al. Diabetes Canada 2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Diabetes in Canada: Diabetes and Mental Health. Can J Diabetes 2018:42(Suppl 1):S130–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2017.10.031.

- Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. Type 1 Diabetes Facts. Available at: https://jdrf.ca/t1d-basics/facts-and-figures/. Accessed April 5, 2024.

- Diabetes Canada. Diabetes and Diabetes-Related Out-of-Pocket Costs - 2022 update. Available at: https://www.diabetes.ca/DiabetesCanadaWebsite/media/Advocacy-and-Policy/Advocacy%20Reports/Diabetes-Canada-2022-Out-Of-Pocket-Report-EN-FINAL.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2024.

Early-stage autoimmune T1D (Stage 1 and Stage 2) represents a disease continuum that begins prior to its symptomatic manifestations. Individuals may have developed two or more autoimmune T1D-associated islet autoantibodies but have normal glycemic levels (Stage 1) or dysglycemia (Stage 2).1

No, these terms are used interchangeably. Labelling this as an autoimmune condition raises awareness on the gradual, progressive nature of the disease and the importance of diagnostic screening for autoantibodies.1,2

A small amount of blood is collected by finger prick or blood draw for assay.2

The assay should screen for multiple autoantibodies such as GADA, IA-2A, IAA, ICA, and ZnT8A, which are predictors of developing autoimmune T1D.2–6

In many parts of Canada, only GADA and IAA are available.

Individuals at any age can develop autoimmune T1D, regardless of their diet or exercise choices. It’s important to remain vigilant. ~90% of newly diagnosed young patients have no family history, according to a 2022 report.5,7 Additionally, 70% of autoimmune T1D cases develop in patients older than 20 years worldwide.8

There was a 15x higher risk of development if one or more family members have autoimmune T1D.10

Family members of someone with autoimmune T1D have a 15x higher risk of developing autoimmune T1D compared to the general population. Screening can identify autoantibodies and indicate the risk of progression to Stage 3 autoimmune T1D. It may also reduce the incidence of DKA at diagnosis.10

Consider referring relatives of individuals with autoimmune T1D for autoantibody testing, as there is a potential familial link to the condition.7,9

Autoimmune T1D is a progressive loss of insulin-producing β-cells. Incidents such as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or noticeable symptoms typically appear at Stage 3 of autoimmune T1D. By recognizing that the condition can be detected at earlier stages, individuals are made aware of the risk of DKA and are prepared for a possible future autoimmune T1D diagnosis.2,7

CI=confidence interval; GADA=glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody; IA-2A=insulinoma-associated-2 autoantibody; IAA=insulin autoantibody; ICA=islet cell antibody; ZnT8A=zinc transporter 8 autoantibody.

- Insel RA, et al. Staging presymptomatic type 1 diabetes: a scientific statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2015;38(10):1964–74.

- Besser REJ, et al. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Stages of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes 2022;23(8):1175–87.

- Kawasaki E. Anti-Islet Autoantibodies in Type 1 Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24(12):10012.

- Punthakee Z, et al. Definition, Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes, Prediabetes and Metabolic Syndrome. Can J Diabetes 2018:42(Suppl 1):S10–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2017.10.003.

- Karges B, et al. A comparison of familial and sporadic type 1 diabetes among young patients. Diabetes Care 2021;44(5):1116–24.

- TrialNet. Stages of Type 1 Diabetes. Available at: https://www.trialnet.org/events-news/blog/type-1-diabetes-staging-classification-opens-door-intervention. Accessed July 23, 2024.

- Sims EK, et al. Screening for Type 1 Diabetes in the General Population: A Status Report and Perspective. Diabetes 2022;71:610–23.

- JDRF. June 2024 newsletter.

- Ekoe J-M, et al. Screening for Diabetes in Adults. Can J Diabetes 2018;42:S16–9.

- TrialNet. TrialNet Recommendations for Clinicians. Available at: https://www.trialnet.org/healthcare-providers. Accessed July 12, 2024.