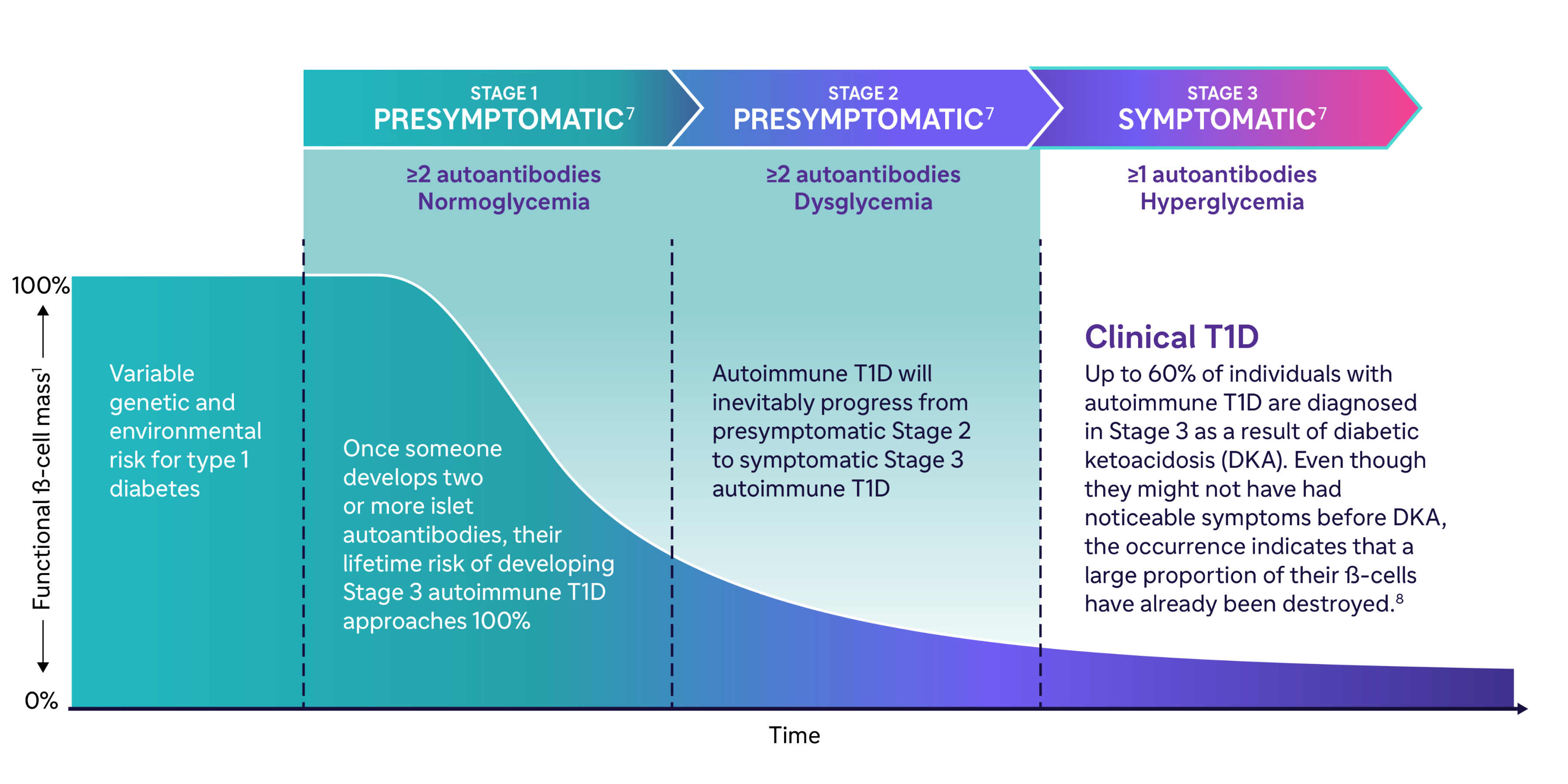

Staging autoimmune T1D

Recognizing presymptomatic autoimmune T1D at the early stages1–3

Autoimmune T1D can manifest from a combination of genetic and environmental factors leading to immune-mediated destruction of pancreatic ß-cells and loss of their function.1

The autoimmune attack driving the progressive decline in ß-cell function in autoimmune T1D starts months to years before symptoms are seen.4 Stages 1 and 2 are presymptomatic and may go unseen until symptoms appear in Stage 3 and the individual is diagnosed with autoimmune T1D.1

Proactive screening in early autoimmune T1D helps to identify individuals who may be at risk.5,6

Autoimmune T1D happens in 3 stages

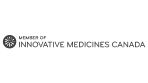

What’s the risk of symptomatic disease?1,2

Early identification of individuals at risk for symptomatic Stage 3 autoimmune T1D may help:

- Insel RA, et al. Staging Presymptomatic Type 1 Diabetes: A Scientific Statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2015;38(10): 1964–74.

- Sims EK, et al. Screening for Type 1 Diabetes in the General Population: A Status Report and Perspective. Diabetes 2022;71:610–23.

- Besser REJ, et al. ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2022: Stages of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes 2022;23(8):1175–87.

- Couper JJ, et al. ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2018: Stages of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes 2018;19(Suppl 27):20–7.

- Barker JM, et al. Clinical characteristics of children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes through intensive screening and follow-up. Diabetes Care 2004;27(6):1399–404.

- Elding Larsson H, et al. Reduced prevalence of diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in young children participating in longitudinal follow-up. Diabetes Care 2011;34(11):2347–52.

- Phillip M, et al. Consensus guidance for monitoring individuals with islet autoantibody-positive pre-stage 3 type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2024 Jun 24:dci240042. doi: 10.2337/dci24-0042. Online ahead of print.

- Beliard K, et al. Increased DKA at presentation among newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients with or without COVID-19: Data from a multi-site surveillance registry. J Diabetes 2021;13(3):270–2.

- Muñoz C, et al. Misdiagnosis and diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes: Patient and caregiver perspectives. Clin Diabetes 2019;37(3):276–81.

- Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. Modeling the total economic value of novel type 1 diabetes (T1D) therapeutic concepts. January 2020. Available at: https://t1dfund.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Health-Advances-T1D-Concept-Value-White-Paper-2020.pdf. Accessed February 2024.

- Scheiner G, et al. Screening for type 1 diabetes: Role of the diabetes care and education specialist. ADCES in Practice 2022;10(5):20–5.